To Love Without Cause

There are many complicated concepts in Judaism.

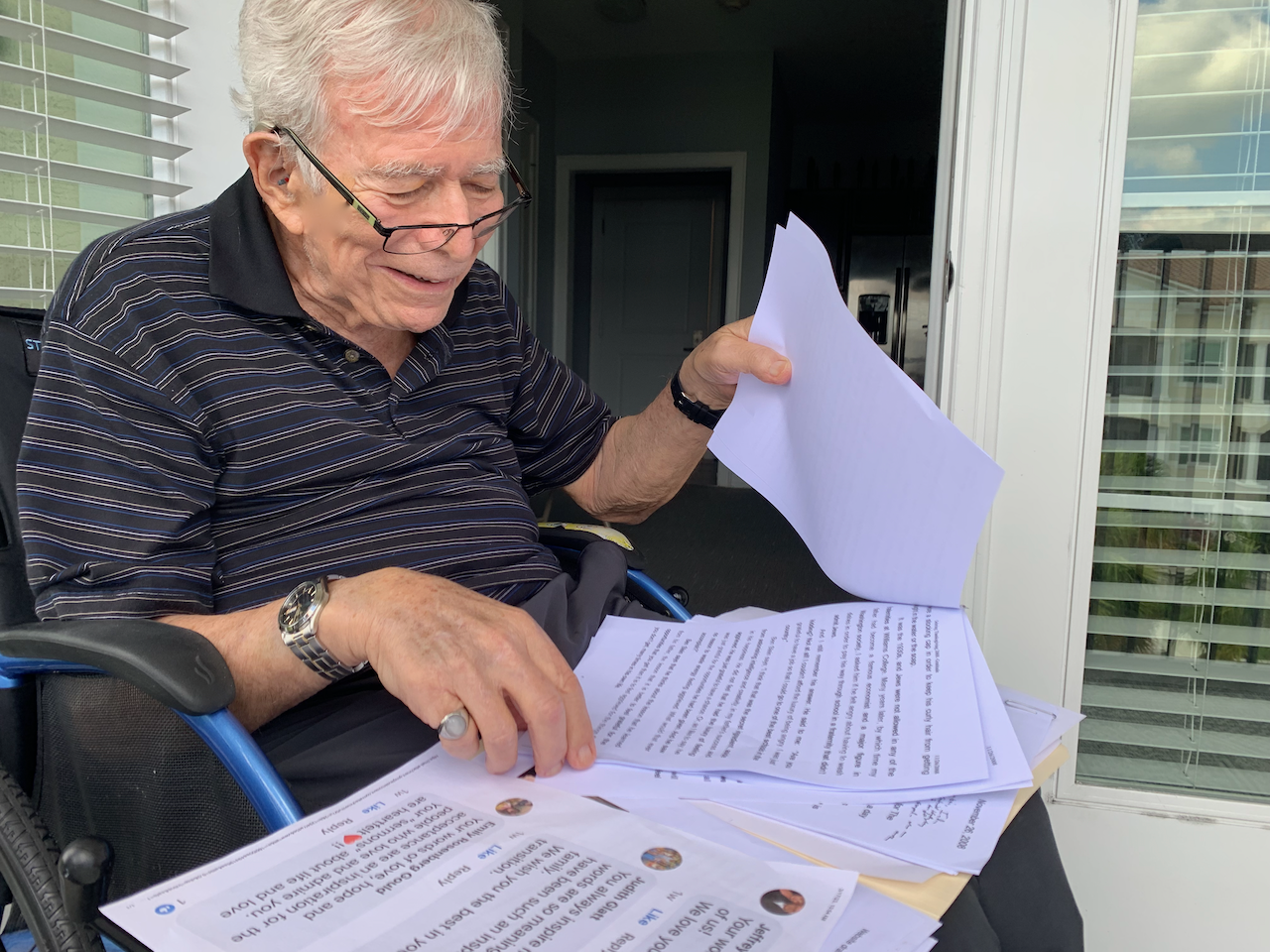

Over the many years of my life in the rabbinate, I have had many struggles and “confrontations with God.” And there are many times when it took me a while to truly understand what I was studying, or found bewildering. Perhaps, you, too, have had such experiences.

Many of my questions and quandaries found renewed energy over the last year as I worked through the revisions of my novel, The Resistance Rabbi and the Gift. One concept that is particularly important to me is: “To Love Without Cause,” as discussed by the Prophet Isaiah.

Yes, I know. Even the title is confusing. But fiction brings us opportunities to create a different path to learn. What follows here is an excerpt from the novel that I hope will help you understand why I believe that being able “to love without cause” is at the very core of how to live well. Perhaps now, more than ever.

The story is set in 1939 and is about a young rabbi who has left his yeshiva to join the Resistance in Poland. War is on the horizon and Eli Morgenstern is struggling with “how to be.” This is Chapter nine.

Chapter 9

To Love Without Cause

December 21, 1938

It was cold and dark in my attic room. I needed to get some rest, but sleep evaded me. There have been so many changes in our world. The meeting at the safe house covered one story after another of the humiliation and degradation of the Jews. Is there anything at all that can stop this madness? Even the windowpanes wept with it. Sorting my thoughts through writing always seemed to help, so I got up, pulled on my coat, and settled at the little desk.

I turned on the lamp, and the bulb flashed and died. I closed my eyes and swallowed my frustration, then found the stub of a candle in a drawer and lit it. I stared at the journal page, pen in hand. I could not find a place to start. So I reached for my Tanakh and opened it to Isaiah:

For the mountains may depart and the hills be removed, but My kindness will never depart from you.

כִּי הֶהָרִים יָמוּשׁוּ וְהַגְּבָעוֹת תְּמוּטֶינָה

וְחַסְדִּי מֵאִתֵּךְ לֹא־יָמוּשׁ

Ki heharim yamushu, vehag'vaot temutena; ve-chasdi me'iteach lo yamush

I’ve read that verse a hundred times, if not more. Tonight it struck me differently, like a whispered answer. Kindness is the answer. But there is nothing simple about kindness in these times. How can kindness continue to exist in the face of violence and terror raining down upon us?

As I turned the pages, I noticed a corner of a scrap of paper was peeking out from under the book cover. Curious to find out what I had tucked away and forgotten, I pulled it out. In the wavering candlelight, I saw that it was folded in thirds. The ink was faded, the Hebrew cursive slanted in a hand I have not seen in years. It was a treasure that instantly lifted my heart.

It was my grandfather’s writing. I had long thought I had lost this special letter and carefully unfolded it to see his familiar writing style, the precise neatness of his work.

He had been Rosh Yeshivah of Piotrków, a giant in Torah, a lion in the Beit Midrash. I was young when he died, but I remember his voice—measured, warm, and confident. I remember, too, the feeling of his hand on my head when he said the words of blessings, and sometimes extra blessings, he said were just for me.

On this parchment, he had written his thoughts on Isaiah in a letter to me. I remember well the day that he handed this to me. I was studying with him for my Bar Mitzvah. I was having a difficult time at school at the time because of some bullies in class who were always giving me a hard time. I was struggling with how I was supposed to behave, how I was to “be” a good person. I remember asking my grandfather, “How am I supposed to love my neighbor if my neighbor hates me?”

He looked at me for a long time, then rubbed his beard and said we had studied enough for that day. Later, after supper, he gave me the letter.

My dear Eliahu,

You pose an interesting dilemma with your questions about ‘how to be,’ as you prepare for your bar mitzvah.

The prophet Isaiah says: ‘The mountains may shift, the hills may fall, but My kindness toward you will not depart, and My covenant of peace will never be broken—so says the Eternal who shows you compassion.’ Do you hear? God’s love is not earned. It does not wait for us to be worthy. It is steadfast. That is ahavat chinam—love without cause.

You asked a very good question when you said, ‘If my neighbor hates me, why should I love him?’ This is the question that generations have debated. The prophet answers—not because your neighbor deserves to be loved by you, but because love that waits for worthiness will never be given. The Holy One loves Israel not for our merit, but because His covenant is love itself. As Isaiah declared, ‘Because you are precious in My eyes, honored and beloved’ (Isaiah 43:4), and again, ‘My kindness shall not depart from you, nor shall My covenant of peace be shaken’ (Isaiah 54:10). To walk in His ways is to give love freely—ahavat chinam—so that hatred finds no home in which to rest.”

The words struck me like a blow. I went back and read aloud the closing: “To walk in His Ways is to give love freely—ahavat chinam—so that hatred finds no home in which to rest.”

These are not abstract words. They are addressed to me, across the years, as if my grandfather had foreseen the world I would face.

אַהֲבַת חִנָּם’

Ahavat chinam— to love without cause.

Now? When the air is thick with venom? Is this not to invite the knife?

And yet—Isaiah’s words burn in me still. My kindness shall not depart from you. If the Almighty’s love could endure wilderness, exile, and even our own failings, perhaps mine could survive the slurs, the spit, the blows in the street. Perhaps ahavat chinam is not a command to feel warmth for my enemy, but a refusal to let hatred take root in my own heart.

I sat back in my chair. The air was so still I could hear the sputtering of the candle’s flame. I was flooded with sadness and nostalgia.

My grandfather knew then what I am only beginning to understand: that the holiness we guard must be rooted not only in law but in love. Without cause. Without reason. Without limits.

Here I sit, writing these words as I struggle to define who I am and what I have become. The world has grown dark and frightening. I don’t know how or if we will get out of this terror. How I wish I could talk with my grandfather now and ask him my questions.

It is easy to love what is lovable. To protect your own. To show kindness when it costs nothing. But that kind of love is expected, earned, deserved, and often transactional. Slowly, my pain eased as it came to me that I must find a new way to look at the meaning of “love without cause.”

Perhaps it is simply that ahavat chinam is what remains when all reason for love has been stripped away. It is love without logic. Kindness without merit. It is how God loves the world, I think — not because we are worthy, but because He is.

Ahavat chinam is not the love of comfort — it is the love of courage. It is not passive. It burns. And perhaps, if enough of us burn with it, we will become the light the darkness cannot smother. Let them say of us one day—not that we hated without cause, but that we loved without needing one.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Merle E. Singer